Abstract

Objective To assess the impact of an intervention initiated by community pharmacists, involving the provision of educational material and general practitioner (GP) referral, on asthma knowledge and self-reported asthma control and asthma-related quality of life (QOL) in patients who may have suboptimal management of their asthma, as evidenced by pharmacy dispensing records. Setting Community pharmacies throughout Tasmania, Australia. Methods Forty-two pharmacies installed a software application that data mined dispensing records and generated a list of patients with suboptimal asthma management, as indicated by having three or more canisters of inhaled short-acting beta-2-agonists dispensed in the preceding 6 months. Identified patients were randomised to an intervention or control group. At baseline, intervention patients were mailed intervention packs consisting of a letter encouraging them to see their GP for a review, educational material, asthma knowledge, asthma control and asthma-related QOL questionnaires, and a letter with a dispensing history to give to their GP. Pharmacists were blinded to the control patients’ identities for 6 months, after which time intervention patients were sent repeat questionnaires, and control patients were sent intervention packs. Main outcome measures Asthma knowledge, asthma control and asthma-related QOL scores. Results Thirty-five pharmacies completed the study, providing 706 intervention and 427 control patients who were eligible to receive intervention packs. Intervention patients’ asthma control and asthma-related QOL scores at 6 months were significantly higher compared to the control patients (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively) and to the intervention patients’ baseline scores (P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively). Symptom-related QOL was significantly higher compared to the control patients (P < 0.01) and activities-related QOL significantly improved compared to baseline (P < 0.05). No significant change was observed in asthma knowledge. Conclusion The results suggest that community pharmacists are ideally placed to identify patients with suboptimal asthma management and refer such patients for a review by their GP. This type of collaborative intervention can significantly improve self-reported asthma control and asthma-related QOL in patients identified as having suboptimal management of their asthma. A larger trial is needed to confirm the effects are real and sustained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of the finding on practice

-

Community pharmacists can effectively utilise their dispensing records to identify patients who may have suboptimal management and control of their asthma and refer such patient to their general practitioner for a review.

-

Community pharmacists and general practitioners can effectively work together to improve patient-reported outcomes in asthma.

-

The sustainability of the impact of an intervention as described in this paper needs to be studied in a larger trial.

Introduction

Asthma is a National Health Priority Area in Australia, and is responsible for significant morbidity and mortality in the community. International population-based studies suggest that Australia has one of the highest prevalence rates for asthma in the world [1], affecting an estimated 2 million people [2]. Despite the existence of national initiatives aiming to improve asthma care [3, 4], significant clinical problems persist, including suboptimal asthma control [5], limited asthma knowledge [6], inferior quality of life (QOL) [7] and poor self-management skills [6].

Due to frequent contact with patients and access to dispensing records, pharmacists are in an ideal position to identify patients who may have suboptimal management and control of their asthma, offer educational material to such patients and refer them to their general practitioner (GP) for a review of their therapy as necessary. Recently conducted studies indicate that Australian pharmacists can deliver interventions to improve asthma control and health outcomes, and patients report high levels of satisfaction with such services [8–10]. However, while the provision of comprehensive pharmaceutical care by community pharmacists has the potential to improve the management of asthma, the uptake into practice is poor, and the need for further research using strategies that are pragmatic in busy community pharmacies has previously been identified [11]. Furthermore, a recent international survey of patients with asthma and their GPs found that too many patients have symptoms that they accept as being part of their condition and many rely too heavily on reliever medication. These findings corresponded with high levels of concern amongst GPs that patients accept their symptoms as normal and frustration that their patients were not more forthcoming about their symptoms [12]. More action is required to encourage patients to view their asthma more seriously and to be more proactive in reporting symptoms to their GP.

Aim of the study

To assess the impact of an intervention initiated by community pharmacists, involving the provision of educational material and GP referral, on asthma knowledge and self-reported asthma control and asthma-related QOL in patients who may have suboptimal management and control of their asthma.

Method

Study design

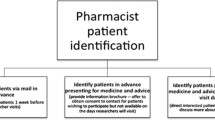

The study, approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Tasmania) Network, was conducted as part of a larger case control study of asthma management, the details of which have been published elsewhere [13]. A software application that seamlessly data mined community pharmacy dispensing records from the market-leading dispensing software system in Australia (Fred Dispense (PCA NU Systems, Melbourne Australia)) was developed. Approximately 50% of community pharmacies in Australia use this dispensing system.

Community pharmacies throughout Tasmania were sent a letter informing them about the project and inviting them to participate if they were currently using the Fred dispensing system. Education sessions for participating pharmacists were held in major regions of the state. These sessions provided an overview of asthma management in Australia, an outline of the project’s objectives and methods, and a demonstration of the data-mining software.

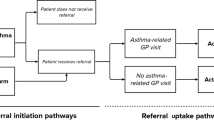

The application was installed in 42 pharmacies throughout Tasmania. Using a pre-specified algorithm, the application identified patients who had received three or more reliever canisters (inhaled short-acting beta-2-agonists) in the preceding 6 months. This indicated that they may have been using on average three or more inhalations per day of reliever medication, which exceeds contemporary guidelines for optimal asthma control [14]. The application randomised the identified patients to an intervention or control group. The participating pharmacists examined the dispensing information for the intervention patients only and excluded those who met the pre-defined exclusion criteria (see Table 1). Pharmacists were blinded to the control patients’ identities until the follow-up phase, 6 months later. In this way it was intended that control patients received no intervention other than the pharmacist’s usual care until this time. Once the pharmacists had deemed the intervention patients eligible for inclusion in the study, they printed materials for each patient using the software application. The materials included:

-

a personalised letter from the pharmacist, referring the patient to their GP for a review of their asthma,

-

asthma knowledge, asthma control and asthma-related QOL questionnaires, and

-

a letter (and dispensing history) to give to their GP.

Supporting educational material provided by the Asthma Foundation of Tasmania (Asthma: the basic facts) [15], was added to the aforementioned materials, and the intervention packs were mailed to all included intervention patients.

The computer-generated personalised letter, which had a standard format, was addressed to the patient and was from the community pharmacist (the researchers did not have access to any identifying details of patients). The letter was designed to be neither alarming nor threatening, and indicated that (i) the pharmacist was concerned that the patient’s asthma may not be ideally controlled, based on the record of medication that had been dispensed recently from the pharmacy, (ii) asthma can be a serious condition and requires ongoing management and close monitoring, and (iii) it would be advisable for the patient to visit their GP and seek a review of their asthma therapy. The computer-generated letter for patients to hand to their GP provided details of the patient’s medication supply over the preceding 6 months. The number of short-acting beta-2-agonists supplied was highlighted as an indicator that the patient may have suboptimal control of their asthma, and may benefit from a review of their condition and current therapy.

Six months after the initial mailing of the intervention packs, the pharmacists discovered which patients were assigned to the control group and excluded any who met the pre-defined exclusion criteria, and any patients who received less than three relievers in the preceding 6 months. Due to ethical considerations, any control patients who were eligible to be included in the study and who were still receiving three or more relievers at this stage were sent an intervention pack. In addition, the intervention patients were sent repeat asthma-related questionnaires at this time.

The de-identified dispensing data from each of the study groups was sent to the project team for analysis before and after the intervention (6-month periods for each). This paper focuses on the changes in asthma questionnaire scores after the intervention.

Questionnaire instruments

The questionnaire assessing asthma-related QOL was based on the Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (MiniAQLQ) [16], a validated 15-item questionnaire designed to measure the patient’s perspective of the impact of asthma on their QOL during the preceding 2 weeks. The MiniAQLQ contains items relating to symptom severity, effects on emotional function, and environmental stimuli, and the limitation of activities. Each domain of the questionnaire allows for calculation of separate scores for symptoms, emotions, environment, and activities, as well as the overall asthma-related QOL score. Higher scores indicate higher levels of asthma-related QOL.

The questionnaire assessing asthma control was based on the Asthma Control Test [17], a validated [18] 5-item test designed to measure the patient’s level of asthma control during the preceding 4 weeks (only 2 weeks was used in this study, in an attempt to be consistent with the MiniAQLQ). Items assess limitation of activities, shortness of breath, night-time symptoms, use of short-acting beta-2-agonists and a self-assessment of asthma control. Higher scores indicate better levels of asthma control.

The assessment of asthma knowledge was based on the Consumer Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire [19], a validated 12-item questionnaire designed to measure the patient’s knowledge of asthma management and medication use. One mark is given for each correct (true/false) answer and zero for each incorrect answer or each question that is left unanswered. Ten items were chosen, and completed questionnaires were scored out of 10, with a higher score indicative of a higher level of asthma knowledge.

Statistical analysis

All questionnaires were coded with unique identification numbers so that baseline and 6-month scores for the intervention patients could be paired. Six-month scores for asthma knowledge, asthma control and asthma-related QOL, as well as the individual QOL domains, within the intervention group were compared to their corresponding baseline scores. Scores for control patients were compared to baseline and 6-month scores for intervention patients.

All variables were collated and entered into a statistical software package (Statview® 5.01; Abacus Concepts Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA). Correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the relationships between each of baseline intervention and control questionnaire scores for asthma knowledge, asthma control and asthma-related QOL. Control group scores were compared to intervention group scores using the unpaired t-test. Baseline and 6-month intervention comparisons were conducted using the paired Student’s t-test and the unpaired t-test. A significance level of P < 0.05 was used for all statistical procedures.

Results

A total of 2,449 patients were identified by the data mining application from 42 pharmacies. Thirty-five pharmacies completed the study, providing 976 intervention patients and 959 control patients. Of the identified patients, 802 patients were excluded by pharmacists (exclusion rate of 41.4%), leaving a total of 706 intervention patients and 427 control patients eligible to receive intervention packs. Of the 706 patients who were sent an intervention pack, 36 (5.1%) were excluded from further contact, leaving 670 patients for 6-month follow-up contact. Of the 36 patients who were excluded from further contact, 4 (11.1%) had their letters retuned to sender, and therefore did not receive an intervention pack. Of the control patients, 422 (44.0%) were excluded from contact because they had subsequently received less than three relievers in the 6-month follow-up period, and hence did not meet the requirements to receive an intervention pack.

There were 95 (13.5%) baseline intervention questionnaires, 116 (17.3%) 6-month intervention questionnaires, and 57 (13.3%) 6-month control questionnaires returned, giving an average response rate of 14.7%. Of the 95 intervention patients who responded to the baseline questionnaires, 45 (47.4%) responded again to the 6-month follow-up questionnaires, enabling paired comparisons.

A significant positive correlation was demonstrated between asthma control and asthma-related QOL scores (r = 0.78, P < 0.0001), while asthma knowledge was not significantly correlated with either asthma control (r = 0.05, P = 0.52) or asthma-related QOL scores (r = 0.03, P = 0.74).

Table 2 displays the control versus intervention patients’ asthma questionnaire scores at baseline and 6 months. No significant differences were observed between baseline intervention and 6-month control questionnaire scores. Analysis of 6-month intervention and control patient questionnaires revealed that intervention patients had significantly higher asthma control (t = 2.6, P < 0.01) and asthma-related QOL (t = 2.2, P < 0.05) scores than the control patients. Intervention patients also had significantly higher symptom-related QOL than control patients (t = 2.7, P < 0.01), with no significant difference in other QOL domains or asthma knowledge.

Paired analysis of baseline versus 6-month intervention questionnaires revealed non-significant improvements in asthma knowledge, asthma control and asthma-related QOL. Unpaired analysis of baseline versus 6-month intervention questionnaires revealed significant improvements in asthma control (t = 3.4, P < 0.001) and asthma-related-QOL (t = 2.0, P < 0.05), as displayed in Table 3. Activities-related QOL was also significantly higher after the intervention (t = 2.0, P < 0.05). There were no significant changes in asthma knowledge or the other individual QOL domains.

Discussion

The implementation of a pharmacist-initiated intervention involving the provision of educational material and GP referral, targeted at patients who may have suboptimal management of their asthma, resulted in improved self-reported asthma control and asthma-related QOL. Intervention patients had significantly higher asthma control and asthma-related QOL scores than control patients 6 months after the intervention. This study provided the opportunity to simplify the timely and targeted identification of patients who may have poorly controlled asthma, as evidenced by the high use of reliever medications. Patients and their GPs were alerted of the fact that the patients’ high use of reliever medication may indicate poor asthma control, in attempt to encourage and promote GP-conducted reviews of asthma management.

There was a relatively small sample size for analysing paired asthma questionnaire scores, given the reliance on having returned questionnaires at both time points from each patient. Paired analyses of baseline and 6-month intervention questionnaires revealed improvements in asthma knowledge, asthma control and asthma-related QOL, although due to the small sample size, the improvements were not statistically significant. However, unpaired analyses of all intervention patients who responded at baseline and all intervention patients who responded at 6 months showed significant improvements in asthma control and asthma-related QOL. The MiniAQLQ has been shown to correlate significantly with asthma control [16, 20]. In turn, the Asthma Control Test has been shown to be reliable, valid and responsive to changes in asthma control over time in patients [18].

Despite the provision of educational material to patients, there was no significant improvement in asthma knowledge at 6 months. Furthermore, whilst there was a significant positive correlation between asthma control and asthma-related QOL scores, asthma knowledge failed to correlate significantly with other scores. Previous studies have found that education programs that offered knowledge but no self-management skills did not improve health outcomes in adults with asthma, indicating that knowledge does not necessarily translate into effective self-management behaviour [21]. It follows that knowledge alone is unlikely to have significant effects on asthma control or asthma-related QOL.

It was not known what proportion of all intervention patients sought a review of their asthma therapy as a result of receiving an intervention pack. The improvements in asthma control may have been GP-initiated, via prescribing additional preventer therapy and/or the development of a written Asthma Action Plan, or patient-initiated, via an increased awareness of their condition with avoidance of trigger factors and/or improved self-management after being alerted to their high reliever usage.

The potential limitations of this study are the low patient questionnaire return rate and the possibility of external factors influencing the results. The average patient response rate of the mailed questionnaires was approximately 15%. This response rate was relatively low, considering that the average patient response rate to postal questionnaires (without reminders or incentives) reported in medical journals is approximately 20–50% [22–26]. The personalised letter that was mailed with the questionnaires encouraged patients to make an appointment with their GP at their earliest possible convenience. Perceived need for a medical consultation, as well as the cost of a consultation and the potential cost of increasing asthma therapy (e.g. the addition of inhaled corticosteroid therapy) may have been barriers to visiting the GP.

We recognise that the low patient questionnaire return rate makes the generalisability of the reported results challenging. Nevertheless, we have previously published the dispensing data analysis of all identified patients which showed positive improvements in the dispensed asthma medications for all patients who received the intervention pack, regardless of whether they returned the questionnaires [13].

The baseline and the follow-up questionnaires were completed 6 months apart, therefore seasonal differences in asthma control may have influenced the results. Colder winter months were represented at baseline, whilst warmer summer months were represented at 6 months. Winter months often result in poorer asthma control [27, 28]. The possibility of this adversely affecting the results was reduced by administering the questionnaires to control patients. Analysis of baseline intervention questionnaires and 6-month control questionnaires did not reveal any significant difference in the scores. It is therefore likely that the improvement in asthma control and asthma-related QOL were due to the intervention rather than seasonal improvement.

Conclusion

Community pharmacists, with their computerised dispensing records and frequent contact with patients, are in an ideal position to identify patients who may have suboptimal management and control of their asthma, provide them with educational material and refer them to their GP for a review. This study has shown that such an intervention can improve asthma control and asthma-related QOL in targeted patients. We recommend that the intervention be trialled on a larger scale, with different levels of community pharmacist involvement, to determine the uptake and effectiveness of such interventions initiated in Australian community pharmacy settings.

References

Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R. The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA dissemination committee report. Allergy. 2004;59(5):469–78. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x.

Australian Centre for Asthma Monitoring 2007. Asthma in Australia: findings from the 2004–2005 National Health Survey. Cat. no. ACM 10. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. ISBN: 978-1-74024-677-4.

Australian Health Ministers’ Conference 2006. National Asthma Strategy 2006–2008. Canberra: National Asthma Council Australia. ISBN: 0-642-82840-7.

Department of Health and Aged Care 2001. National Asthma Action Plan 1999–2002. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. ISBN: 0-642-44734-9.

Marks GB, Abramson MJ, Jenkins CR, Kenny P, Mellis CM, Ruffin RE, et al. Asthma management and outcomes in Australia: a nation-wide telephone interview survey. Respirology. 2007;12(2):212–9. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.01010.x.

Matheson M, Wicking J, Raven J, Woods R, Thien F, Abramson M, et al. Asthma management: how effective is it in the community? Intern Med J. 2002;32(9–10):451–6. doi:10.1046/j.1445-5994.2002.00273.x.

Goldney RD, Ruffin R, Fisher LJ, Wilson DH. Asthma symptoms associated with depression and lower quality of life: a population survey. Med J Aust. 2003;178(9):437–41.

Armour C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Brillant M, Burton D, Emmerton L, Krass I, et al. Pharmacy asthma care program (PACP) improves outcomes for patients in the community. Thorax. 2007;62(6):496–502. doi:10.1136/thx.2006.064709.

Kritikos V, Armour CL, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ. Interactive small-group asthma education in the community pharmacy setting: a pilot study. J Asthma. 2007;44(1):57–64. doi:10.1080/02770900601125755.

Saini B, Smith L, Armour C, Krass I. An educational intervention to train community pharmacists in providing specialized asthma care. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(5):118.

Weinberger M, Murray MD, Marrero DG, Brewer N, Lykens M, Harris LE, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacist care for patients with reactive airways disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(13):1594–602. doi:10.1001/jama.288.13.1594.

Bellamy D, Harris T. Poor perceptions and expectations of asthma control: results of the international control of asthma symptoms (ICAS) survey of patients and general practitioners. Prim Care Respir J. 2005;14(5):252–8. doi:10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.04.003.

Bereznicki BJ, Peterson GM, Jackson SL, Walters EH, Fitzmaurice KD, Gee PR. Data-mining of medication records to improve asthma management. Med J Aust. 2008;189(1):21–5.

National Asthma Council Australia 2006. Asthma Management Handbook 2006. South Melbourne: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. ISBN–13: 978-1-876122-07-2.

Asthma Foundations Australia. Asthma: The Basic Facts. Asthma Foundations of Australia 2006. http://www.asthma.org.au/Default.aspx?tabid=91. Cited June 2008.

Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of the mini asthma quality of life questionnaire. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(1):32–8. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a08.x.

Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.. 2004;113(1):59–65. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.008.

Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Nathan RA, et al. Asthma control test: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(3):549–56. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.011.

Kritikos V, Krass I, Chan HS, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ. The validity and reliability of two asthma knowledge questionnaires. J Asthma. 2005;42(9):795–801. doi:10.1080/02770900500308627.

Chen H, Gould MK, Blanc PD, Miller DP, Kamath TV, Lee JH, et al. Asthma control, severity, and quality of life: quantifying the effect of uncontrolled disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(2):396–402. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.040.

Gibson PG, Powell H, Coughlan J, Wilson AJ, Hensley MJ, Abramson M, et al. Limited (information only) patient education programs for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;2:CD001005.

Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC. Effectiveness of various mailing strategies among nonrespondents in a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131(6):1068–71.

Hoffman SC, Burke AE, Helzlsouer KJ, Comstock GW. Controlled trial of the effect of length, incentives, and follow-up techniques on response to a mailed questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(10):1007–11.

Brealey SD, Atwell C, Bryan S, Coulton S, Cox H, Cross B, et al. Improving response rates using a monetary incentive for patient completion of questionnaires: an observational study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:12. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-12

Perneger TV, Etter JF, Rougemont A. Randomized trial of use of a monetary incentive and a reminder card to increase the response rate to a mailed health survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138(9):714–22.

Brogger J, Nystad W, Cappelen I, Bakke P. No increase in response rate by adding a web response option to a postal population survey: a randomized trial. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(5):e40. doi:10.2196/jmir.9.5.e40.

Chen CH, Xirasagar S, Lin HC. Seasonality in adult asthma admissions, air pollutant levels, and climate: a population-based study. J Asthma. 2006;43(4):287–92. doi:10.1080/02770900600622935.

Pendergraft TB, Stanford RH, Beasley R, Stempel DA, McLaughlin T. Seasonal variation in asthma-related hospital and intensive care unit admissions. J Asthma. 2005;42(4):265–71. doi:10.1081/JAS-200057893.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participating patients, community pharmacists and GPs. Members of the Project Working Group, Dr Keith Miller, Sue Leitch, Guy Dow-Sainter, and Sharyn Beswick were all invaluable in our project design and implementation. We would also like to thank Dr James Markos, Cathy Beswick and Melanie Blackhall.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing and the Asthma Foundations Australia. via an Asthma Targeted Intervention Grant.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bereznicki, B.J., Peterson, G.M., Jackson, S.L. et al. Pharmacist-initiated general practitioner referral of patients with suboptimal asthma management. Pharm World Sci 30, 869–875 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-008-9242-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-008-9242-3